Bedsores (decubitus ulcers)

Medically reviewed by Drugs.com. Last updated on Jul 28, 2023.

What is a bedsore (decubitus ulcer)?

Bedsores, also called pressure ulcers or decubitus ulcers, are areas of broken skin that can develop in people who:

- Have been confined to bed for extended periods of time

- Are unable to move for short periods of time, especially if they are thin or have blood vessel disease or neurological diseases

- Use a wheelchair or bedside chair (a hospital chair that allows a patient to sit upright next to the bed).

Bedsores are common in people in hospitals and nursing homes and in people being cared for at home. Bedsores form where the weight of the person's body presses the skin against the firm surface of the bed.

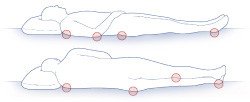

In people confined to bed, bedsores are most common over the hip, spine, lower back, tailbone, shoulder blades, elbows and heels. In people who use a wheelchair, bedsores tend to occur on the buttocks and bottoms of the feet.

This pressure temporarily cuts off the skin's blood supply. This injures skin cells. Unless the pressure is relieved and blood flows to the skin again, the skin soon begins to show signs of injury.

The pressure that causes bedsores does not have to be very intense. Normally, our skin is protected from being injured by pressure because we move frequently, even when asleep.

Where bedsores occur

At first, there may be only a patch of redness. If this red patch is not protected from additional pressure, the redness can form blisters or open sores (ulcers). In severe cases, damage may extend through the skin and create a deep crater that exposes muscle or bone.

Muscle is even more prone to severe injury from pressure than skin. A bedsore can involve several layers of damaged tissue.

Although pressure on the skin is the main cause of bedsores, other factors often contribute to the problem. These include:

- Shearing and friction — Shearing and friction causes skin to stretch and blood vessels to kink, which can impair blood circulation in the skin. In a person confined to bed, shearing and friction occurs each time a person slides across the bed sheets.

- Moisture — Wetness from perspiration, urine or feces makes skin under pressure more likely to suffer injury. People who can't control their bladders or bowels (people who are incontinent) are at high risk of developing bedsores.

- Decreased movement — Bedsores are common in people who can't lift themselves off the bed sheets or roll from side to side. Without these small movements throughout the day, skin that is pressing against the bed does not get a steady supply of oxygen and nutrients. Blood flow is inadequate in these parts of the skin. (People who can move without assistance have a lower risk of bedsores because they can shift their weight periodically.)

- Decreased sensation — Bedsores are common in people who have nerve problems that decrease their ability to feel pain or discomfort. Without these feelings, the person cannot feel the effects of prolonged pressure on the skin.

- Circulatory problems — People with atherosclerosis, circulatory problems from long-term diabetes or localized swelling (edema) may be more likely to develop bedsores. This is because the blood flow in their skin is weak, even before pressure is applied to the skin.

- Poor nutrition —Bedsores are more likely to develop in people who don't get enough protein, vitamins and minerals.

- Age — Elderly people, especially those over 85, are more likely to develop bedsores because skin usually becomes more fragile with age.

Bedsores can lead to severe medical complications, including bone and blood infections.

Symptoms of a bedsore

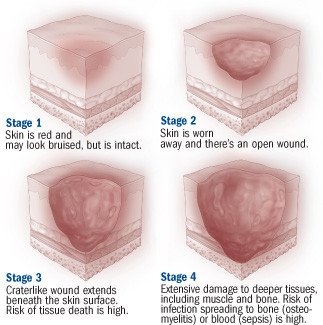

Bedsores are classified into stages, depending on the severity of skin damage:

- Stage I (earliest signs of skin damage) — White people or people with pale skin develop a lasting patch of red skin that does not turn white when you press it with your finger. In people with darker skin, the patch may be red, purple or blue and may be more difficult to detect. The skin may be tender or itchy, and may feel warm or cold and firm.

- Stage II — The injured skin blisters or develops an open sore or abrasion that does not extend through the full thickness of the skin. There may be a surrounding area of red or purple discoloration, mild swelling and some oozing.

- Stage III — The ulcer becomes a crater and that goes below the skin surface.

- Stage IV — The crater deepens and reaches into a muscle, bone, tendon or joint.

Because broken skin can allow bacteria to enter, bedsores are extremely vulnerable to infection. This is especially true if the sore is contaminated by urine or feces. Signs of infection in a bedsore can include:

- Pus draining from the sore

- A foul smelling odor

- Tenderness, heat and increased redness in the surrounding skin

- Fever.

Diagnosing a bedsore

A doctor or nurse can diagnose a bedsore by examining the skin. Testing is usually unnecessary unless there are symptoms of infection.

If a person with bedsores develops an infection, a doctor may order tests to find out if the infection has moved into the soft tissues, into bones, into the bloodstream or to another site. Tests may include blood tests, a laboratory examination of tissue or secretions from the bedsore, and an x-ray, a magnetic resonance imaging scan (MRI scan) or a bone scan to look for evidence of a bone infection called osteomyelitis.

If you care for a family member who is in a bed or wheelchair, your doctor or home care nurse can teach you how to identify the earliest signs of bedsores. You'll learn which areas of skin are particularly vulnerable and what to look for. When you find signs of skin damage, you can take steps to prevent areas of redness from becoming full-blown ulcers.

Expected duration of a bedsore

Many factors influence how long a bedsore lasts, including the severity of the sore and the type of treatment, as well as the person's age, overall health, nutrition and ability to move. For example, there is a good chance that a Stage II bedsore will heal within one to six weeks in a relatively healthy older person who eats well and is able to move. Stage III and Stage IV ulcers can take longer than six months to heal. Some never heal. Bedsores can be an ongoing problem in chronically ill people who have multiple risk factors, such as incontinence, the inability to move and circulatory problems.

Preventing a bedsore

Bedsores can still form even if a patient is receiving excellent medical care or household care — they are not necessarily a sign of neglected needs. To help prevent bedsores in a person who is confined to a bed or chair, the plan of care includes these strategies:

- Relieve pressure on vulnerable areas — Change the person's position frequently, when possible every two hours when in bed and every hour when sitting in a chair. Use pillows to raise the person's arms, legs, buttocks and hips. Relieve pressure on the back with an egg-crate foam mattress, a water mattress or a sheepskin. Two types of beds — air-fluidized beds and low-air-loss beds — have been shown to reduce the likelihood that a pressure ulcer will form.

- Reduce shear and friction — Avoid dragging the person across the bed sheets. Either lift the person or have the person use an overhead trapeze to briefly raise his or her body. Keep the bed free from crumbs and other particles that can rub and irritate the skin. Use sheepskin boots and elbow pads to reduce friction on heels and elbows. Wash the person gently. Avoid rubbing or scrubbing the skin.

- Inspect the person's skin at least once each day — Early detection can prevent stage I redness from becoming worse.

- Minimize irritation from chemicals — Avoid irritating antiseptics, hydrogen peroxide, povidone iodine solution or other harsh chemicals to clean or disinfect the skin.

- Encourage the person to eat well — The diet should include enough calories, protein, vitamins and minerals. If the person cannot eat enough food, ask your doctor about nutritional supplements.

- Encourage daily exercise — Exercise increases blood flow and speeds healing. In many cases, even bedridden people can do stretches and simple exercises.

- Keep the skin clean and dry — Clean with plain water and if needed a very gentle soap. Use absorbent pads to draw moisture away from vulnerable areas. If the person is incontinent, ask your doctor about ways to control or limit the leakage of urine or feces.

Treating a bedsore

If you care for someone with bedsores, your doctor or home care nurse may ask you to help with the treatment by following preventive steps that should stop further damage to vulnerable skin and increase the chances of healing.

Additional treatments, usually done by health care professionals, depend on the stage of the bedsore. First, areas of unbroken skin near the bedsore are covered with a protective film or a lubricant to protect them from injury. Next, special dressings are applied to the injured area to promote healing or to help remove small areas of dead tissue. If necessary, larger areas of dead tissue may be trimmed away surgically or dissolved with a special medication. Deep craters may need skin grafting and other forms of reconstructive surgery.

If the person's skin shows any signs of possible infection, the doctor may prescribe antibiotics, which may be applied as an ointment, taken as a pill or given intravenously (into a vein).

When to call a professional

If you find a suspicious area of redness or blistering on a person you are caring for, contact the person's nurse or doctor promptly.

Prognosis

In many cases, the outlook for bedsores is good. Simple bedside treatments can heal most stage II bedsores within a few weeks. If conservative methods fail to heal a stage III or stage IV bedsore, reconstructive surgery often can repair the damaged area.

Additional info

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

https://www.niams.nih.gov/

National Institute on Aging

https://www.nia.nih.gov/

American Academy of Dermatology

https://www.aad.org/

Further information

Always consult your healthcare provider to ensure the information displayed on this page applies to your personal circumstances.